Voices of Pashtun Women from Wartime Afghanistan

Arnold R. Isaacs

July 16, 2014

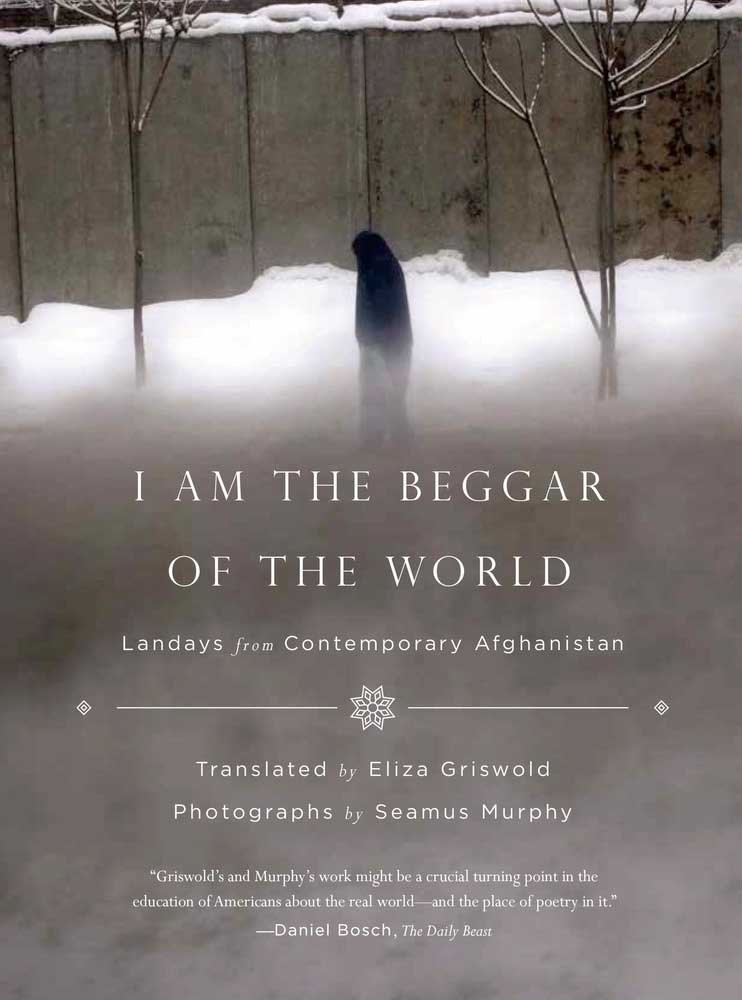

I AM THE BEGGAR OF THE WORLD: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan Translated by Eliza Griswold, photographs by Seamus MurphyFarrar, Straus & Giroux. 149 pages, $24 |

|

This unusual book gives a voice — though a fragmented one — to a group of people who usually remain unheard. The voice belongs to the women of Afghanistan’s largest ethnic community, the Pashtuns. We hear it in short, two-line snatches known as landays, a traditional form of folk poetry in which Pashtun women for many generations have expressed themselves from behind the veils that hide their faces.

Landays are an oral art. In Pashto, they are customarily sung, not spoken (a custom that itself can at times be an act of defiance, since music-making, particularly by women, is viewed as anti-Islamic by religious extremists like the Taliban). They come in many tones, from romantically lyrical to acidly sarcastic to bawdily humorous. The oral tradition also makes them fluid creations, with subjects and language constantly evolving to reflect events and changing conditions in society. Thus the examples — exactly 100, by my count — in this collection present a sometimes jarring mix, some sounding completely timeless while others come straight from today’s global culture. Two pairs of landays from the chapter called “love” illustrate the point. The first two come out of traditional village life, and could have been composed today or hundreds of years ago:

Darling, come down to the river,

I’ve baked you bread and hidden it in my pitcher.

Climb to the brow of the hill and sight

where my darling’s caravan will tent tonight.

The second pair show how the world of today has penetrated even to Afghan villages:

Come, let’s leave these village idiots

and marry Kabul men with Bollywood haircuts.

How much simpler can love be?

Let’s get engaged now. Text me.

The landay tradition exists on both sides of the Afghan-Pakistani border — in fact, Pakistan’s Pashtun population considerably outnumbers Afghan Pashtuns — but the ones in this book were all collected in Afghanistan, and thus unavoidably are in part a chronicle of the 35-year catastrophe of war, destruction and flight that has been Afghanistan’s recent history. The devastation of those years is reflected in the subject headings Eliza Griswold used to arrange her landays: after love, they are grief, separation, war, and homeland.

Griswold, the author of a terrific book called The Tenth Parallel: Dispatches from the Fault Line between Christianity and Islam (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010), is a journalist in the tradition of what used to be called literary journalism. Her research on landays began after a magazine assignment in 2012 to write about the death of a young Afghan woman who was beaten by her brothers for writing poetry, which they considered was a dishonor for their family; after the beating she set herself on fire, and died of her burns. On that and a subsequent trip, Griswold — at times covering herself in a burqa so as not to be identified as a foreigner — sought out women who let her copy down landays they knew or had composed, and then, in a collaborative effort with Pashtun colleagues, crafted these translations. The English versions, mostly rhymed couplets, do not strictly follow the Pashto forms, which have a prescribed number of syllables (nine in the first line, 13 in the second) and are often unrhymed. But Griswold, who is also a poet, sought to capture the tone and feeling of the landays as she heard them. Without knowing Pashto it is impossible to be sure exactly how close she came to that goal, but the selections in this book certainly have an authentic ring.

They ring with something else, too: a deep contradiction between pride in Pashtun traditions and culture and history, and bitterness at the suffocating restrictions those same traditions and culture impose on women’s lives. Some couplets celebrate the Pashtun code of honor and its glorification of the warrior:

Who will you be but a brave warrior,

you who’ve drunk the milk of a Pashtun mother?

But the same code is also seen as oppressive and cruel:

You sold me to an old man, father.

May God destroy your home, I was your daughter.

There’s no way to know if those and similar examples reflect the thoughts of different women with different ideas and feelings, or how much they may represent an inner conflict in Pashtun women’s hearts and minds. That is one of many things one can guess Griswold must have learned more about than she discloses in the very spare text of this book. Presumably she wished to keep the focus on the landays, but along with admiration, I read this book with a growing sense of frustration that she did not share more of what she found while collecting them.

Reading I Am the Beggar of the World will give no comfort to those who thought the U.S. military intervention in Afghanistan would be gratefully received by Afghan women as a benevolent blow against their oppression. The Americans certainly promote more enlightened attitudes than the Taliban, and as Griswold points out, some U.S. aid and civil development projects are aimed at expanding women’s freedom and opportunities. But in these couplets, Americans are associated only with drone strikes, home raids, detentions, and an unwanted foreign military presence, all regarded with fear, anguish, defiance and hate:

My Nabi was shot down by a drone.

May God destroy your sons, America, you murdered my own.

Leave your sword and fetch your gun

Away to the mountains, Americans have come.

These are specifically Pashtun voices, from the ethnic group that is the backbone of the Taliban. Different attitudes might be heard from Tajiks, Uzbeks and other Afghan communities. But even with that qualification, the message from this book helps explain why U.S. military power, in Afghanistan and in other contemporary conflicts, has been such an uncertain weapon.

Some 50 photographs by Seamus Mitchell accompany the text. They don’t really illustrate it, however, in the sense that they are not related to the landays, their subjects or the women who sing them. Though Mitchell traveled with Griswold on both her trips to gather material for the book, almost none of these photographs are from those journeys either; with only three or four exceptions, they are from earlier assignments in Afghanistan. That can be seen in the list of dates and place names that appear at the back of the book. Beside that list, though, we have no other information about the photographs, since there are no captions. Presumably the idea was to put the printed words into a kind of landscape, surrounding them with visual scenes of Afghan life and terrain. Many of the images are indeed arresting, but the lack of captions mirrors a larger issue with the book: a nagging sense that it could have told us much more than it does about the women’s world from which these couplets come.

The writer of The Tenth Parallel is clearly a reporter of great talent, who surely learned more about that world behind the veil than is found in this collection. I am sure I am not the only reader who hopes she will share more of that knowledge in future writing.

Arnold R. Isaacs is the author of From Troubled Lands, Listening to Pakistani and Afghan Americans in post-9/11 America.