Islam’s Clash of Beliefs, As Seen From Modern Iran

February 3, 2015

Soon after she first began working with foreign journalists in Tehran, Nazila Fathi was summoned to the Intelligence Ministry to be questioned about her activities. She approached the interview with trepidation, but in the end the ministry cleared her for an official permit to continue her work. The Iranian authorities were suspicious of international media but, Fathi writes, found some value in allowing them to give the outside world a somewhat balanced impression of life under the revolutionary regime. As she saw it, their reasoning went like this:

“Ever since the revolution, Western governments and media outlets had demonized Iranians, portraying them as armed men and black-clad women chanting, ‘Death to America.’ But there was so much more to Iran than this. There was life beneath the surface; there were ordinary people all over the country who longed for freedom and dignity just as people did in any other part of the world. Even though the regime aimed to stamp out these impulses, it had also realized that, by spreading evidence of them around the world, people like me were helping improve the country’s image.”

That aim — giving a more rounded, varied view of her country and its now 60 million people — is also the central theme and achievement of this memoir.

A Lonely War opens in 1979, when Fathi was nine years old. That was the year when a popular uprising overthrew the U.S.-backed Shah Reza Pahlavi and installed a theocratic revolutionary regime led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. From that beginning, the book chronicles the next three and a half decades of the Islamic Republic of Iran as Fathi experienced them, first as a teenager, then as a young translator and “fixer” for foreign journalists, and eventually as the full-time Tehran correspondent for the New York Times until threats from the authorities forced her to flee into exile in 2009.

The country we see through Fathi’s lens is a place of astonishing contradictions. It calls to mind the clinical description of what psychiatrists used to call Multiple Personality Disorder, in which “two or more distinct identities or personality states are present, each with its own relatively enduring pattern of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and self.”

Fathi does not use psychiatric terms, but her description is similar: “Two different cultures lived side by side in our country; one was modern and relatively secular, the other traditional and intensely religious. The 1979 revolution had nurtured the hostility between these two different strains of Iranian culture by encouraging the religious people to police secular people, to dominate their lives by telling them what they must and must not do.”

Beside showing the conflict between those two cultures, Fathi’s experiences and her reporting on the larger society also show that Islamic fundamentalism in Iran is not the same as the Taliban in neighboring Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Iranians may be strict, even brutal, about such issues as modest dress for women (Fathi was once sharply reprimanded for wearing white socks, which she was warned “would draw men’s attention to your ankles”) but unlike the Taliban, they don’t seek to keep girls uneducated. Quite the opposite: Fathi reports the remarkable statistic that the literacy rate among young rural women more than quadrupled in less than 20 years following the revolution, from 19 percent before 1979 to 86 percent in 1996. In the country as a whole, literacy has become virtually universal over the life of the Islamic Republic, rising from 56 percent before the revolution to 99 percent today. Women are thriving in higher education too; currently, more than 60 percent of the students in Iran’s universities are female.

In other respects, too, Iran’s religious leaders do not match the common stereotype of Muslim extremists as across-the-board opponents of modern life and scientific progress. Iranian clerics embraced the computer revolution quite early in their own, Fathi notes, establishing a computer research center for Islamic studies in Qom, Iran’s religious center, as early as 1988. That center evolved into one of the country’s first Internet centers, where clerics sit at computers translating and digitizing religious texts and answering e-mailed questions from Muslims around the world. Fathi’s description may surprise readers who think of Muslim fundamentalists as uniformly backward and primitive:

“I saw clerics walking around in their socks in a carpeted room and perching in front of boxy monitors. To make themselves more comfortable, some of the clerics rested their turbans on the desk next to the monitors they were using, giving them a slightly more relaxed look.” Most of the e-mail questions, she found, were about sexual problems, not religious doctrine.

Islamic fundamentalism in Iran is not the same as the Taliban in neighboring Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Iranians may be strict, even brutal, about such issues as modest dress for women but unlike the Taliban, they don’t seek to keep girls uneducated.

Fathi’s narrative follows the course of major events after the revolution: the traumatic eight-year war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in the 1980s; rising demands for reform in the following decade (from some remarkable women advocates for women’s rights, among other activists); the election of the relatively liberal president Mohammad Khatami in 1997 and the wave of repression that overtook his reforms in the decade’s closing years; and a continuing seesaw of reform and repression in the 2000s. The upheavals after the questionable 2009 national election of Mahmoud Ahmedinejad as Iran’s president, when mass protests erupted against the apparent rigging of that election, were the last story Fathi covered in Iran. Her attempts to cover the demonstrations and the brutal government crackdown brought her under increasing pressure and the threat of arrest, and in mid-2009 she and her family left for exile first in Canada and then in the United States.

In parallel with those political events, Fathi’s memoir also documents changes of another kind that have transformed Iranian life and society since the revolution. Some of these were technological: the introduction of satellite TV and the Internet, which opened new windows on information and ideas. Others were social and economic, mostly made possible by wealth from oil revenues. The revolutionary regime did not only spend time and resources on policing women’s dress and men’s beards; it also presided over (or was swept along by) a dizzyingly swift transformation of Iran into a predominantly middle class country. Fathi pictures that change as having weakened the regime’s base; as they acquired more material comfort and had more interaction with the outside world, many Iranians became less inclined to support the authorities’ suffocating control of personal conduct and their strict version of Islamic belief and practice.

The story told in The Lonely War is, obviously, unfinished. The struggle between Iran’s different personalities continues, with important implications for the Middle East and the rest of the world. But if it does not tell us how the struggle will end, Fathi’s account is a useful reminder that the clash of beliefs and cultures is at its core a conflict within the Muslim world, not between Islam and the West. Americans are of course affected in a great many ways by that conflict, but they would do well to remember that winning or losing the “war of ideas” is not in American hands. A wise U.S. policy must begin with understanding that reality and the nature of the different forces involved. In this book, Nazila Fathi has made a valuable contribution to that understanding.

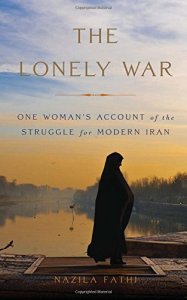

THE LONELY WAR: One Woman’s Account of the Struggle for Modern Iran

by Nazila Fathi

Basic Books, 297 pages, $27.99

Arnold R. Isaacs is a journalist and writer. He has written two books on the Vietnam war and is also the author of From Troubled Lands, Listening to Pakistani and Afghan Americans in post-9/11 America.